the ultra-wealthy are addicts.

We’re Being Led By Addicts

We’ve seen a parade alarming of headlines in recent years and months: Elon Musk is set to become the world’s first trillionaire. Wealth inequality in the United States has exceeded the gap seen prior to the French Revolution. The rapid expansion of the artificial intelligence sector is generating massive amounts of money for the few as jobs for the many get eliminated.

This unyielding forward slog of wealth accumulation seems to be dooming us all. AI data centers waste massive amounts of drinkable water to put out just a few seconds of subpar video, carcinogenic microplastics have been found in almost every part of the human body, and global warming at its current clip is set to cause significant portions of the globe to become uninhabitable.

However, it would seem that the ultra-wealthy are not reveling in their success, nor are they concerned for the gloom of our shared futures: instead, the behavior of those in power has seemingly been getting worse and worse over time: the gradual uncovering of the Epstein files have revealed international sex trafficking schemes that seem to have touched the figureheads of nearly every major industry, and the long-rumored “human safari” pay-to-kill schemes in Sarajevo during the 1990s Bosnian genocide have received new attention as evidence has been uncovered.

To the average person, to continue on a luxurious slide toward planetary death sounds unfathomable and irrational. And why would you turn to harming others on purpose when you have the means to do anything else? What’s the pathology of wanting more and more, regardless of the harm and the risk? There’s not one, singular answer, but I do have an idea for one of them. Extreme wealth accumulation is an addiction. We are living in a global social and political system ruled and managed by addicts*.

Money, Hierarchy, Power, and the Brain

I live in Seattle, Washington. Thanks largely to the tech industry, my county is home to over 54,000 millionaires and 12 billionaires, and the city itself is the seventh wealthiest in the United States. Unsurprisingly, I see a lot of Teslas and Cybertrucks around town. Tesla drivers have earned themselves a reputation for being assholes—no matter how many of them choose to label their cars with anti-Elon bumper stickers as a protection against vandalism. Similarly, when I lived in Spokane years ago, I experienced similar poor driving from the owners of pricey, pristine, lifted trucks, who would tailgate and speed constantly.

As it turns out, there’s social science that backs up the rude behavior of wealthier drivers. Psychologist Paul Piff conducted a study on aggressive, selfish behavior among drivers at particular crossroads and then recorded the make and model of the cars. Those commandeering expensive and luxury vehicles were four times more likely to cut someone off and three times more likely to fail to yield to pedestrians. Meanwhile, drivers of the cheapest cars were significantly more likely to yield and much less likely to cut someone off. Further research by Piff showed that richer study subjects were more likely to engage in antisocial behaviors such as stealing, owed to underlying beliefs of entitlement and superiority. In other words: wealthier people feel like they deserve to do whatever they want, whenever they want, with little regard for others (if not outright disdain).

While wealth may not be the root of all evil, it’s often at the scene of the crime. This is because wealth and social hierarchy are closely entwined. Rank and status are extremely important in social species, particularly for reasons of safety and access to resources. This makes changing and safeguarding rank a major motivator of behavior. A recent study from the University of Texas at Austin found that male mice with high social rank whose status was lowered exhibited high levels of stress: the more dominant the position, the more changes within the brain when experiencing a demotion. If the pattern of behavior and brain activity exhibited in the mice holds true for humans, this may provide important explanations for the entitled and defensive behaviors among the very wealthy seen when changes in wealth status are suggested or enforced, such as changes in tax schemes or pushes for unionization.

However, this was a study of mice. What do we know about hierarchy and the human brain? Researchers from the Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience studied the effects of hierarchy on moral behavior and found that extreme hierarchy emboldens harmful actions, as it splits agency and empathy. You likely already knew this—the affect of hierarchy on moral behavior was exemplified in the famous Nuremberg defense offered by Nazis interrogated for their crimes during the Holocaust: “I was just following orders.”

The Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience researchers found that when assigned the positions of “commander” and “intermediary”, study participants at the social brain lab exhibited lower activation in empathic brain regions when inflicting pain, compared to participants who were not ranked. Essentially, when we are operating alone and directly, we take responsibility and empathize more with those we inflict harm on. Conversely, when we are operating in a ranked system, we remove ourselves from responsibility and thus empathize less.

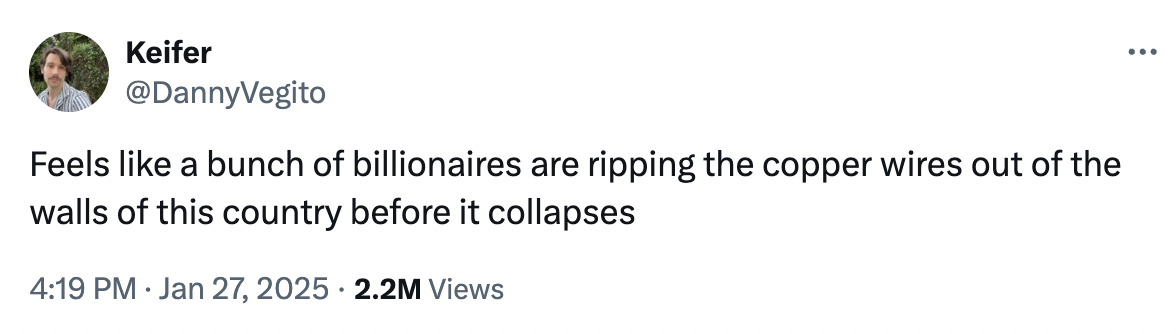

To me, the combination of these two studies would imply that hierarchy can create a self reinforcing loop of behavior for those at the top. Billionaire CEOs conducting mass layoffs and sending former employees into poverty and millionaire politicians slashing SNAP and Medicare for vulnerable families are detached from the on-the-ground reality of what their choices do to others because those policies are enacted through lower rank employees or individual agencies. Accordingly, they are not inclined to care nor to take responsibility for their impact. Additionally, the threat of having their rank jeopardized can drive this behavior further as part of an attempt to maintain or safeguard their position: CEO and executive suite pay climbs and companies register record profits as mass layoffs abound and wages stagnate, and the ultra wealthy shovel money into causes and policies designed to manufacture consent and manipulate citizens into voting against their own interests.

We know, then, that wealth and hierarchy can complicate moral judgement. But this affect extends past the defensive and status-protective behavior that humans make when we—correctly or incorrectly—perceive risk and threat. Wealth is both connected with addiction and can be addictive in itself. On the micro level, children of affluent parents are more vulnerable to substance abuse issues and the rich consume 27% more alcohol than the poor. However, this is not the crux of my concern. Instead, the addictiveness of the pursuit of wealth itself is where I would like to turn next.

A Brief, Layman’s Overview of How Addiction Works

Addiction to the accumulation of wealth is not a typical chemical dependency. Some addictions, rather than a physical reliance on a substance as seen in alcohol and drug addictions, are a compulsive relationship to a set of behaviors. If you have ever watched My Strange Addiction, you have seen a few of these at work. See below for the infamous guy who was “in love” with his car as one, niche example. More commonly, gambling, food, sex, and shopping can all become addictions. These are known as behavioral or process addictions: with all addictions, the ingestion of a substance or performance of a set of behaviors rewards the brain with an influx of chemicals such as dopamine that generate a high. The pursuit of extreme wealth fits into this pattern, and I am by no means the first one to say so: Clinical psychologist Dr. Tian Dayton wrote the same in his 2009 Huffpost opinion piece. As he said:

“It's general wisdom that for someone who is addicted to alcohol or drugs, their lives become increasingly organized around the use and abuse of their substance. The person who uses money to mood alter can have their relationship with money spin out of control; by being overly focused on accumulating it, spending it hoarding it or using it to control people, places and things.”

It’s worth pointing out that the accumulation of money, for the average person, delivers diminishing returns for happiness. In a Princeton University study conducted in 2008 and 2009, money “bought” happiness up to around a salary of $75,000 per year. With inflation, it’s quite a bit higher now, but the broader point stands: When you have enough money to care for all your basic needs and to relieve strain, more money will not make you happier. Unless, of course, you have developed an addictive and compulsive relationship with it akin to a substance.

Whether chemical or behavioral, addiction works through some of the same brain mechanisms. I am a layperson to this, so take my very simplified explanation with a grain of salt (and read my sources for this piece, which are linked at the bottoms of this page)**: The brain is made up of billions of neurons, which are organized into the overlapping networks and circuits that control different aspects of our physical system, perceptions, motivations, and emotions. Neurons speak to each other via neurotransmitters communicated through synapses, which prompt changes in the receiving cell via receptors. Drugs interfere with the communication process—some possess a chemical structure similar to that of neurotransmitters like dopamine, which are naturally produced by the body, leading to neuron activation and abnormal messages being communicated between cells. Others can prompt neurons to release natural neurotransmitters, but far too much: this can prevent the normal use of brain chemicals, which amplifies or disrupts normal communications between neurons.

Due to this, most if not all of the brain is impacted. In particular, the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex are affected. The basal ganglia is heavily involved in what is colloquially as the brain’s reward circuit: i.e., the part of the brain that motivates through pleasure and other positive forms of motivation. Drugs over-activate it, generating a euphoria, but repeated exposures diminish its sensitivity and require a higher and higher dosage for the same experience. The extended amygdala, which deals in stressors such as anxiety and irritability, becomes increasingly sensitized through drug use and contributes to feelings of withdrawal, further motivating continued usage. Lastly, the prefrontal cortex (notably, one of the last parts of the brain to reach full maturity) manages impulse control, problem solving, and decision-making. All in all, the picture is one where an addict requires an ever-increasing dosage and frequency to achieve euphoria and avoid feelings of withdrawal, while also possessing less and less ability to manage the impulse to use—or, to engage in risky behavior that relates to their ability to access the substance.

The above has been a (very barebones) explanation of addiction to chemical substances, such as alcohol or illicit drugs. Behavioral addictions are not exactly the same, but both function by overloading the pleasure and reward systems of the brain. Pleasurable activities in general activate these sections of the brain, and normally this is a good thing. Most activities we can engage do not generate such an extreme reaction. For example, I exercise regularly and benefit from the endorphins—this motivates me to continue going and as a result, I improve my strength, flexibility, and cardiovascular health. I also experience dopamine by connecting socially with my friends and building closer bonds. But because these pleasure chemicals are not overloading these brain systems, I do not develop a compulsive or addictive relationship with exercise or socializing.

For our purposes here, I want to use gambling as a bit of a mini, pseudo-case study. In addition to the factors involved with behavioral addictions mentioned above, gambling addicts have been noted to have lesser brain activity in the brain’s ventral striatum when anticipating financial rewards, motivating impulsive behavior. Beyond the relationship between dopamine and the reward centers of the brain, gambling addicts may be more heavily affected by volume and activity in other regions of the brain, such as those managing learning and stress management. Additionally, the randomness of the gambling process provides a higher risk and higher reward, but at random intervals. But since humans are naturally pattern-seeking, this can cause those prone to gambling addiction to see each loss as a step closer to a reward, keeping them looped into the behavior whether they win or lose. And because these are addictions, a higher and higher reward will be needed in order to generate the same “high”, requiring that the gambling addict put more money into the pot.

The reason I bring up gambling addiction as my example is because I see it as connected to the addictive behaviors the ultra-rich exhibit toward wealth accumulation. Both deal with money as the “reward” through what is basically gambling. Nowadays, the difference is largely a matter of scale: the poors gamble at casinos and through sports-betting apps, and the rich gamble through the stock market and through other means of market manipulation. On an official level, the market is not a casino or a locale for gambling, but poor management and enforcement of consumer protections make it one. Deregulation, government bailouts, insider trading, and speculative trading have fostered an environment that motivates short term gains rather than long-term sustainability. Practices like day trading mimic gambling in particular. Again, I am not the only person to say so—Warren Buffet has said so at least twice in his annual letter to shareholders:

“For whatever reasons, markets now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young. The casino now resides in many homes and daily tempts the occupants.”

Conclusions?

The issue with the very, very wealthy is that their extreme power allows them to manage their losses by manipulating their would-be checks: buying out and paying off politicians as one such example. Their extreme wealth also makes it difficult to achieve a “high” from any win, leading to more and more extreme behaviors with less and less regard for impact on others, or on the world at large. As chemical dependency worsens, addicts may resort to behaviors such as stealing from family members or burglarizing strangers in order to generate the capital needed to obtain more drugs. It isn’t different here. Generating wealth at that massive of a scale requires the exploitation of something—workers, consumers, and natural resources. It requires deception, scamming, and overuse. Where a severe enough addiction can cause an individual person to overdose and pass away, the intermingling of money and power in a global economic system dependent on constant growth and accumulation ties all of our fates together.

I won’t go too deep into the details here, but the rate of environmental destruction we are currently seeing through pollution, deforestation, and global warming has already led to and will continue to cause mass tragedy. Heat waves and rising sea levels are making certain regions of the world unlivable. We are already in the midst of a mass extinction event and ecological diversity is declining rapidly. This environmental damage is ongoing because it benefits the financial interests of multinational corporations and their leadership. Long-term, we cannot continue like this. It will not be possible for life to continue as we know it—and as we depend on it—if our economic and power systems remain as they are. If the short term minded, addictive, and hierarchy-driven behaviors of the ultra-wealthy remain in place, we will all fall of the cliff together.

Unfortunately, the damage incurred by this economic system does not stop at environmental damage. If a financial win generates a lower and lower dopaminergic return in the ultra-wealthy’s brain’s pleasure and reward centers, it’s also likely that they will seek out new behaviors and activities that may activate that segment of their brains in a new way. Wealth is, after all, a stand-in for power, making activities that relate to hierarchy, control, and dominance an attractive next step—for more than just the reasons I mentioned in the earlier section. I hesitate to bring this up due to the nature of it, but I believe that the severely antisocial and abusive behaviors we have seen out of the wealthy connect to these addictive tendencies. P. Diddy and his “freak-offs”, the Sarajevo killings, and Jefferey Epstein’s global child sex trafficking are a few recent examples. In particular, I think of Epstein and his documented behavior, particularly as we learn more through the release of files on his case. The combination of rank and status-protective actions, entitlement, superiority, and behavioral addictions motivate more and more extreme behavior: both to generate blackmail against the only other people who can threaten your place in the hierarchy (as a type of mutually-assured destruction), and to generate the power-trip high that comes with breaking our most fundamental taboos with impunity. The fear and cageyness seen among those in Trump’s camp regarding the release of the files is two-fold: the blackmail material can’t serve as a threat if it’s been deployed and exposed, and the ability to get their “fix” will be jeopardized if people are aware of how they’ve done it.

I know for a fact that I am not the only person who has been witnessing the world with the sense that a boiling point is near. My entire life has been characterized by rapid technological change, but in the past decade that I have been an adult, there has been an intensifying speed to it: I have watched my government pull itself apart structurally. I have witnessed surveillance creep into every aspect of my life. I have seen the seasons change and winter begin to fade. At the same time, I have seen a transformation in people’s consciousness: not always for the good, but often so. I have felt the change in myself; this desire for things to change at the root. Things cannot go on like this, and so they won’t. It’s true that we have all been locked into a system we didn’t ask for, that doesn’t benefit us, and that threatens our lives and livelihoods. But it’s also true that we aren’t doomed. One idea that gives me some comfort now is that of extinction bursts: that in the death of a particular set of behaviors, it increases in rate or intensity before it ends. For every push forward, there is a desperate reaction to maintain the status quo, but ultimately these responses are weak and suggest few of their own ideas, providing little reason for people to cling tightly to them. In time, they fail. My hope is that as more of us continue to hold the line against the system as it is, we will be able to remake the world in a way that works for all of us: not just the few at the very top.

Notes:

* I am trusting that whoever reads this does NOT interpret my use of the word “addict” as derogatory toward those struggling with addiction. Addiction is multifaceted, with a variety of biological and social causes. I use the word a descriptor for the purposes of discussing a set of behaviors. Please, no bean-souping.

** I am not an expert on addiction and do not want to be interpreted as one. This piece is me fleshing out and exploring an idea—given who I am talking about, it isn’t terribly likely that it’s going to get studied directly, but it’d be fantastic if it were. And don’t read this piece as medical advice or guidance. Especially since I didn’t give any. I just have an IR degree. But, uh, don’t do drugs, kids.

Sources:

Netherlands Institute of Neuroscience: What is the effect of hierarchy on moral behavior?

Greater Good Magazine: How Money Changes the Way You Think and Feel

Harvard Health: Understanding Addiction: How Addiction Hijacks the Brain

Stanford Medicine: Why our brains are wired for addiction: What the science says

National Library of Medicine: Definition of Substance and Non-substance Addiction

The personal project of perfection

More of my life than I’d like to admit has been spent trying to figure out to attain perfection. It wasn’t phrased as or sold to me in that packaging, though. It came in the way of diets and beauty products, books and groups, fitness regimes and journaling prompts. There was constantly another new thing on the horizon, tantalizingly offering itself as a solution to a problem I hadn’t yet known I had. Somehow, my life became a type of permanent improvement project, and I was on a wilderness expedition to constantly suss out and eliminate whatever else I found wrong with me. It was a story that started younger than I can remember. I don’t think I’m the only one.

There was a perfect storm or an unfortunate soup of factors that led to that reality for me (and maybe for you too): growing up evangelical in a community with fundamentalist leanings, the idea that the soul could approach near-perfection through doctrinal purity and correct outward behavior was forever lingering in the background. The recitation of verses, unquestioning devotion to the right beliefs, endless consumption of Christian media, and appropriately monitored hemlines and hearts were the path forward, and absolutely, constantly necessary. The perpetual self-flaggelation required to reinforce that view came first, though. Nothing motivates the breathless search for the secret sauce of salvation quite like the fear that if you don’t, you’ll either miss something amazing or you’ll be sent downstairs to be tortured in perpetuity.

In the world outside, unfortunately, things weren’t much better. It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg dilemma when it comes to the culture’s obsession with becoming “the best version of ourselves we can possibly be”. Combine the so-called Protestant work ethic with the endless pit of hunger that is colonization, and the conditions were born for unfettered capitalism to unhinge its wide maw around every aspect of life. We are nowadays surrounded by a “secular” forever improvement-oriented culture, spurring a fervor of new and flashy products and courses to give perfect complexions and perfect careers. Promises of being able to attain things as tangible as sportscars and a fat bank account get muddled with the more esoteric: love, respect, and power. And of course, these are understood as the natural rewards waiting for those who deserve it. To be good is to work and to have the evidence of success in your hands. In the words of Britney Spears, you better work, bitch.

And similarly to the religious world, the shiny carrot-on-a-stick of perfection was paired with a threat. Rather than hell, the threat lingering on the horizon, should you fail to reach toward perfection adequately, is that you deserve whatever horrible fate befalls you. Poverty, powerlessness, ugliness, and/or being unlovable and unworthy of respect due to the aforementioned traits. If hard work makes you “holy” (read: rich and successful), then a lack of holiness must imply laziness. Whatever happens to you, regardless of the details, is your fault for being the kind of person that couldn’t overcome it. To me, it seems popular culture didn’t get too far from its religious roots.

These ideas have even made their way into the close and personal world of mental, emotional, and psychological wellbeing as well: i.e., “healing journeys”. The term has become popular in the last several years among Gen Z and Millennials, as social media has served as a platform to discuss feelings and experiences in a way that has not been possible before. As people have been able to compare notes and access information, there has been a growing appetite to get to the root of our issues rather than numbing or suppressing our way through them. I’ve been no exception. Whether picking apart culturally ingrained ideas or trying to heal childhood wounds, I’ve spent the bulk of the past near-decade in the process of understanding. Pulling up the weeds that have been ingrained into us is, in my opinion, necessary: from culture, schooling, religion, family, and politics, we have indeed received messaging that is flat out incorrect, and serves to do us harm. Unexamined, these ideas flow into subsequent generations, creating a cycle of damaged relationships to self and others. For the sake of our own wellbeing, a bit of introspection is necessary. And so I have tried: doing the reading, doing the therapy, and trying to fix what I didn’t break. As I’ve realized recently, the need to become a perfect worker bee or religiously pure in order to deserve existence is included in that undoing.

Unfortunately, ridding myself of the desire to become perfect has been one of the harder pieces to extricate. It has a way of seeping into every aspect of life. It poisons everything, contrary to what its name implies, perverting simple pleasures into opportunities for improvement, and making the very things that are most human about us disappointing and unenjoyable. It has left me stuck and analyzing my life, thinking back on minor interactions as if I was a surgeon holding a scalpel. Because I hadn’t thought about it much at the outset of my “healing journey”, I hadn’t necessarily anticipated that this impetus toward attaining perfection would follow me this far. Perhaps I should’ve known: after all, it’s easy to combine all of these strains of perfection-seeking together. It becomes a three-headed hydra: I’ll save myself through becoming infallible on the inside, and then everything else good I want will follow naturally.

This impulse isn’t completely without reason: it IS easier to prioritize things like eating a healthy meal and getting enough sleep when your nervous system is calm and you can self soothe (through behaviors other than binging ultraprocessed foods, or staging a mutiny against rest via revenge bedtime procrastination). It IS easier to know your own likes and dislikes regarding personal style, career path, and general lifestyle when you aren’t chronically disconnected from your feelings. But it isn’t true that it delivers unto you flawless beauty, total respect from others, or even naturally smooth relationships. In many cases, emotional skill-building and mental healing make you less compliant, less tolerant, and a worse fit for the demands of modern life. Your emotional sphere can come back into appropriate focus in a way that demands that you care for yourself and others in ways that are inconvenient or even detrimental to certain areas of life. You become less likely to comply, submit, and acquiesce to mistreatment or abuse. You become less willing to betray your values. This aspect of becoming well-rounded and whole carries certain risks. It can lead to a less polished, shiny life than what the perfectionism game tries to promise you. For this reason, the drive to become perfect on the inside has a way of bringing a real healing journey to a shuttering stop in the middle of the road.

It stagnates as sort of a navel-gazing waiting game. If we believe it is possible or necessary to attain some impossible summit, we will continue to consume new ways to become better and better: another self help book, another psychologist lecture on YouTube, another yoga meditation course, another flip through the tarot cards, another therapeutic modality. In the pursuit of figuring out what ELSE might be wrong with us, we miss what is right with us, and we miss opportunities to actually live our lives, out of fear that we haven’t gotten far enough in our “healing” to deserve it. We resign ourselves to becoming some kind of voluntary outcast, climbing into towers to wait for one last thing that finally rescues us. Instead of the carrot on the stick being religious salvation or material riches, we gatekeep ourselves from connection.

And the thing about the drive to become perfect–both in the religious sense and the American hustle/consumer culture sense–is that you are never, ever allowed to take your foot off the gas. You cannot stop moving. There is no such thing as resting–until you’ve earned it. It would be one thing to get stuck in a tricky spot and use it to recuperate, but if ascension to “godliness” is the goal, real rest is not allowed. To stop for long enough to contemplate would be to backslide or allow the possibility of a backslide. Progress is meant to be linear and measurable. In this paradigm, becoming the best we can never requires slowness or ceasing the perpetual wave of consumption. It never asks of us that we sit down and let things be.

But the idea that you can rescue yourself out of the human condition via hard work is ultimately futile. Imperfection in all its types is what it means to be a person. No matter how much shadow work or inner child work you do, the shadow and the inner child remain a part of you. They will have their moments: a slip of the tongue, or a heated comment, a rash decision. Old ideas you thought you’d washed away will pop up in your mind, surprising you with their presence and requiring your attention yet again. You’ll sleep through alarms, avoid the gym, eat a microwave dinner and watch too much TV, forget to wear sunscreen, and slack off at work. It might happen less, maybe, but it will happen.

It occurs to me, now, that whatever stage is next for me, I cannot escape both acceptance of flaws and the need to slow down. I think most of us have spent some time, at least once, watching a chrysalis hang at the edge of a branch, with the vague knowledge that a transformation was underway. Or seen a baby sleep, knowing that with each passing second they were growing, though imperceptible to the naked eye. Genuine change, particularly the type that people most need in a culture that demands that we deaden our souls to comply with the endless drain of end-stage capitalism, is a messy and slow metamorphosis. That process is exhausting. It demands rest. And it does not follow a path that is easily monetized or easily explainable. For this reason, it runs headlong against perfection culture. A well-rested and self-actualized person is not a ready consumer or producer. They may watch new wrinkles form in the corners of their eyes with curiosity, not disdain. They may take a moment to breathe rather than work for someone else’s bottom line. They may relax about their flaws long enough to let go of the need to race on an endless hamster wheel of self-improvement. And, in the process, open the door to real, genuine healing, humanity, and community.

At least, that’s what I’ve been finding out for myself.

The most human duty

Amidst the breadth of suffering we’ve seen in the last several months of this exhausting year— the destruction of Medicare, the mass layoffs of crucial federal workers, the dismantling of political alliances, harsh rollbacks on trans visibility and rights and the tearing apart of families by masked and armed ICE agents, to name just a few— I’ve seen discussions circulating around empathy: that conservatives struggle with empathy, that white guilt is actually the impulse to feel empathy, that our culture has a severe lack of empathy among certain generations and groups, etc. And it’s got me thinking about what precisely the issue is with empathy in the United States.

For me, this question has some roots: I grew up hearing “bleeding heart liberal” utilized as an epithet against the left, with the implication that their empathy was well-intentioned but ultimately illogical and ridiculous: an achilles heel that led them to make stupid decisions that would at some point result in disaster or waste. Empathy was chuckled at as childish and juvenile. An abundance of it was seen as a sign not of moral strength but as an indication of poor fitness for leadership. As it would turn out in the years to come, this was a kinder view. These days, it’s openly ridiculed and denigrated as weakness by the right. Why? The full reason is more expansive than I can cover fully now or here. But I want to offer some of my thoughts.

Over the past year or so, I’ve read several books that have touched on the ideas of care, community, and connection: The Last Human Job by Allison Pugh, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Eve by Cat Bohannon, and The Good Ancestor by Roman Krznaric, to name a few. Each in their own way, these authors discussed themes of long-term thinking both in terms of history and the future, how connective and emotional labor functions in the workplace, and how these themes are a fundamental aspect of what it means to be a human being.

On the other hand, I have also read Cultish by Amanda Montell and Why Does He Do That by Lundy Bancroft: the first of which discusses how cults utilize language to manipulate their adherents, and the second of which explains what motivates abusers and how they enact abuse on their victims. What has struck me from the combination of these two books is the potential for severe perversion and manipulation of basic human impulses: the twisting and turning upside down of relationships by a dysfunctional and unequal power balance. The message I have been left with as a result of reading works such as these is this: Human beings are made for each other. A disruption or perversion of humanity’s ability to relate is a critical injury that enables atrocity. They cannot happen without it. From the Holocaust to Jonestown to the separation of children from their parents at the U.S. border and the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, all have been enabled by dysfunction in human relating.

Humans have a natural impulse to empathize. Even babies as young as six months can empathize, as was demonstrated in research published in the British Journal of Psychology in 2019. The infants in the study demonstrated a clear preference for a character who had been harmed in a skit over the neutral character- despite only having barely developed object permanence around this time. On the other hand, we have a fundamental need to receive empathy, alongside our impulse to deliver it to others: other studies have shown throughout the years that connection with caregivers and consistent responsiveness to the needs of babies and children is critical to their well-being and ability to thrive. Beyond this, emotional regulation skills cannot be taught without empathetic mirroring: i.e., the simple acknowledgement, naming, and acceptance of one’s feelings from another party. This is to say: we learn both who we are and how to relate to others through empathy.

The deep necessity of empathy and connection go further than childhood. In the broad history of humanity we see tribal groups expand and survive through cooperation, eventually settling and developing agriculture and large civilizations, along with inventions and innovations we still use today. I have seen this described as purely utilitarian in nature before- as though the advancement of humanity throughout the world was motivated primarily by a you-scratch-my-back-I-scratch-yours arrangement, driven by survival-of-the-fittest in a ruthless and individualistic competition for survival. And no doubt a tit-for-tat dynamic (or elements of outright force) did play out during many major achievements, such as the construction of the Egyptian pyramids or the Roman plumbing system.

However, for each example of selfish self-interest working together or compelling the actions of others, we have examples of (what would be considered) unnecessary empathizing that marched in lockstep. Archaeological and other historical findings have shown that throughout history, and in times of scarcity when it would have been dangerous to do so, we have cared for the elderly, sick, and disabled members of our communities. In 2007, the 4,000-year-old remains uncovered in Burial 9 in Hanoi, Vietnam revealed a young man with a type of congenital segmentation disorder, which paralyzed him during childhood and would have caused significant neurological impairment, also potentially limiting his ability to chew. Despite being unable to feed, clean, or clothe himself as his condition progressed, he lived into his thirties. This finding, while striking, isn’t alone. In another example, a young female skeleton was discovered on the Arabian peninsula, dated to more than 4,000 years ago. She likely had a condition such as polio, with indications that she likely could not walk and required constant care. Going beyond exhibiting empathy in her daily care, her community likely fed her dates or other sugary foods, to such an extent that her teeth were cavity-ridden. They not only cared for her needs, but cared for her happiness.

To those who see human history as dog-eat-dog, this behavior may seem strange or unreasonable. After all, if our deepest desires are simply to proliferate our genes forward, wouldn’t resources best be spent on those that can materially contribute? Isn’t this empathizing dangerous? Isn’t it against our interests? In my opinion, no. Rather than reflecting the reality- that empathizing is fundamental to human community building, survival, and safety- it has been treated frequently in the U.S. as illogical and weak. Empathy has been cast off into the domain of the feminine, assisting its portrayal as minimally important, frivolous, or outright pathetic. A strict gender binary that categorizes communally-oriented and empathetic behavior as feminine and weak also categorizes self-motivated and individualistic behavior as masculine and strong: creating a distinction that does not truly exist. Empathy is not male or female, nor is it illogical. Empathy is profoundly logical: We are strongest together. In a world where the forces of nature and the forces of the powerful few can impose suffering and hardship on us, it only makes sense to pool resources and look out for each other, gathering the knowledge and motivation we need to continue from our community. This seemingly “illogical” behavior of caring for others, even when difficult, serves a deeper purpose: tying us together and motivating us to continue. In short, it gives us our will to live.

Because empathy has the power it does, it serves as a threat to those wanting to make exclusive claims to rule and dictate. For that reason, the powerful have few more important tools in their kit than separation, division, and the demonization of others. It is in the interest of those who want to elevate themselves above and outside of the broader human family that people tell themselves isolating fictional stories about how “real” men are rugged individuals that go it all alone, or that white people are some kind of master race that are meant to rule others. It’s beneficial to them to twist the historical narrative to be a story of notable individuals, such as in Great Man Theory, which posits that history is moved forward primarily by individual men destined for greatness, rather than by the diverse opinions, interests, reactions, and actions of all people, working together over time (and that eventually birth and cultivate those individuals). This ahistorical perversion of how the world works stymies progress by zapping people of their power in multiple ways: it keeps people away from those they would otherwise learn from and partner with, it reduces their capacity for rest and the accumulation of resources by necessitating that they work more for less gain, and demotivates them by obscuring the reality of other peoples’ lives. When you do not know and love your neighbors, you cannot share resources or understand their struggles, and you cannot gather the knowledge and strength needed to resist.

This is precisely why, for example, wealthy white landowners and enslavers were so deeply threatened by actions such as John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, or why Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by the FBI as he began to speak out more firmly against capitalism. These actions provided support for potential collaboration, uniting people with a common goal and understanding of their place in the power structure, and against the power of racism by dismantling the separation it imposes on artificially manufactured racial groups. Similarly, as other justice movements advance, such as gay and trans rights, feminism, Palestinian liberation, and disability rights, more people understand the fundamental similarities and common interests we share as regular people.

As we empathize and unite against common enemies and challenges to imagine and build a better world, those in power lash out and struggle harder to separate us. Young men are fed red-pill incel content online, and white teenagers are served racist and homophobic dogwhistles and tropes denigrating their non-white and LGBTQ classmates. Americans in general get siloed into entirely separate media diets, with white conservatives constantly consuming unsubstantiated conspiracies and outright lies, while everyone, at bare minimum, is consuming half-truths that obscure the nature of power. Then, the enemy isn’t the billionaire executive cutting your insurance coverage or the multi-millionaire boss replacing your role with a shoddy AI. It’s not the multinational corporation shipping jobs overseas, or the U.S. empire wasting tax dollars invading and destabilizing other countries, or the rising threat of homelessness pushed by private equity buying up family homes. It’s immigrants or drug addicts or minorities or women or trans people or gay people. It’s your neighbors.

That isn’t to say that those who buy into the propaganda aren’t culpable for their harm. They are. From white nationalists to anti-trans campaigners to those cheering on ICE raids, they are responsible for their actions and for the support they lend to oppressors. They have a responsibility to break with their groups in favor of the truth, and I know this because I’ve done it: I came from the conservative Christian world that elected Trump, and I left it behind in 2016 as an 18 year old college freshman because of its moral contradictions and embrace of bigotry (this, as I came to realize, had been present the entire time. I’d just been too insulated to see it until then). However, it is to say that their behavior would not be possible without the dismantling and demonization of their natural human impulse to empathize. Those that stick most closely to the American mythos— that it is a Christian country founded on freedom, that white Americans are superior and entitled to dominance, and that success is merit-based— have built an identity that is too fragile for criticism. Rather than having an identity that is connected to a deep and broad sense of community, theirs is narrow and based on adherence. You belong to your group, but only as long as you pass a constant flow of loyalty tests to prove your allegiance to the group and against outsiders, largely by forming an identity around being non-empathetic.

I began my break away from conservatism when I started to question sexism in the church and when I started, out of curiosity, to listen to the experiences of trans people. Leaning into my empathy created a rupture that was inoperable. All ruptures are inoperable in these groups. Comply, or get banished. They are desperate to belong somewhere- after all, they have the basic human need to belong. Like all cults do, conservatism nowadays takes advantage and perverts these drives. Empathy becomes dangerous and terrifying because it requires two things: to change their identity, and to take action against oppression. To embrace empathy, they must walk headfirst into cognitive dissonance, into the isolation that comes from breaking with the fold while not yet being safe to accept into a new one, and into the shame and guilt that stems from realizing that not only have you been wrong and manipulated: you have caused deep harm. I have walked that walk. I will be grateful for it for my entire life, but it was difficult.

Conservatives fear empathy because empathy requires responsibility and accountability. Responsibility and accountability require being seen and evaluated by others, receiving their criticism, and making amends. And then, continuing to dedicate efforts to doing better in real, tangible ways. It takes an ego death to shed allegiances to white supremacy, capitalism, American exceptionalism, sexism, homophobia, or other framework that falsely imposes hierarchy and creates divides. Whatever this may look like, when this duty is accepted, we are able to return to ourselves as empathetic human beings, removing the barriers placed between ourselves and others. To truly return home to empathy is to recognize your place in your community, locally, nationally, and globally. It is to accept empathy as the most human duty.

Saying goodbye.

Note: This was written in mid-January

Before you get worried, no, I’m perfectly fine. This isn’t a cry for help or anything to be concerned about. But it is a closing chapter of sorts, in the sense that you need one of those to start the next book in the series. I’ve been re-evaluating my life a lot lately, and the conclusion I’ve come to is that it’s time for me to divest from the things that sap my energy and my joy in order to reinvest in the things that truly make life worth living. Maybe you relate to this. Or not- but either way I invite you to hear me out.

The last several days I’ve been sick with one of the nastiest head colds I’ve had in awhile. It might be RSV or the flu. Either way, I’ve spent a lot of time lying flat on my back with nothing to do except scroll on my phone, hack up a lung, or sleep. It turns out the crushing weight of the world and the crushing weight of a viral load don’t go all that well together. As I’ve gotten older, social media and the intensity of online life has begun to feel overwhelming, like a constant droning background noise that’s hard to escape but hard to resist. I’m only human: I want connection, I want to know what’s going on, I want to laugh, and I don’t want to miss out on an opportunity I might only find if I stay stuck there, scrolling and hoping and wondering what’s next. But the cost has become too high. I get tense and aggravated every time I see an advertisement and the beginning of certain songs now make me grit my teeth from the sheer overplay (R.I.P., Too Sweet by Hozier, among others).

Now, I find myself missing the internet of my childhood. Not in its entirety, mind you- the internet of my childhood was a bit too lawless. Elementary schoolers were watching LiveLeak videos of people getting their heads blown off, girls were getting groomed on Kik, and kids were getting flashed on Omegle. But I miss the fractured nature of it. There were sites specifically for children, where we’d play educational flash games in much the same style we’d play a game offline. Or, if we were curious about particular topics, we’d find message board sites for that interest. Those still exist, but social media has become so all-consuming over the last ten to fifteen years that it’s difficult to think of what the internet even is without it. I miss when the internet was a place- a computer that you visited for an hour or two a day if that, and then closed down and left behind while you went about living the rest of your life. When I was young, it was a refuge from my life and a way to connect with people outside the bubble I felt constrained and trapped in. But since then I’ve built a life I don’t need to escape from, and my relationship to the internet and social media has become a drain.

So I began culling things. Over the past year or so, I mass-deleted from my following list and cut my own followers from most of my accounts, and made most of them private. I set time limits on my phone for most apps. While it did make things better by cutting down on the noise, It didn’t help as much as I hoped it would. Instead of honoring the limits I set, I found myself bypassing them to pass time when I was bored. Or, I was finding new nonsense to look at and respecting the letter but not the spirit of the rules I’d set for myself. It would take a larger motivation to finally and fully push me to do differently.

The final few months of 2024 were difficult for me, for reasons I won’t detail here. It’s hard to wrap my mind around the year, or create a coherent image of what it was like without separating it into a dichotomous before and after. I won’t say now that things are better per se, but they are different. Very different. What transpired caused me to reframe and reflect, hurrying along at a greater intensity and clip thought processes that were already in play. People pleasing and fawning behaviors I’ve struggled my entire life to understand and rid myself of came to light and got unceremoniously squashed. I got angry again. I realized that I’d quietly tolerated far too much and for no real benefit. So, fuck it.

Around the same time, the 2024 election occurred, the TikTok ban has come barreling down the track, Elon Musk is apparently the pseudo-president now, and Meta is cozily in bed with the incoming government. So, suffice it to say, it’s felt lately like there’s little reason to hold on anymore. Over the years, I’ve created and abandoned I don’t know how many random accounts on how many random sites I don’t even remember exist anymore. What’s one or two more to add to the pile?

I want boring internet and an exciting life. I want to be engaged with the world, even if it seems like it’s burning. I want to visit this place and then leave it behind when I’m finished with it, rather than living passively in the passenger seat as I’ve driven along into endless consumption. I’ve seen more than enough ads convincing me I need a new viral sweat set on Amazon or gel pens on TikTok shop. I don’t need it, and neither do you. I need my life to be something.

So I am going away and saying goodbye. To an extent- I’m staging a partial exodus from Instagram and Facebook and returning to the old internet. I used to have a little Blogspot blog and a Tumblr blog back in the day where I’d write my thoughts down and then leave them behind. I’m older now and it isn’t quite the same, but I want to create a space to write out my thoughts without seeing who’s seen them or monitoring for comments. Those who care, can, but otherwise it’s okay if it just sits mostly unseen. It’s for me, and that’s alright. There’s no obligation to it for me or anyone else. This is a part of something bigger for me.

2025 has loomed large for me. I’m not a super strong astrology girl, really, but my Saturn return is coming up in a few months and I’m willing to take it as a sign of new beginnings. I feel as though all my life has been preparing me to be 27 and ready for something- as though all of the bullshit and reforming and reorienting and redoing I’ve had to do so far was to make me the person I needed to be for the rest of my life. Starting now. Which, sure, is a very strong statement to make. But I get to make it true, don’t I?

I’m going to be present here sometimes so I can be present in the rest of my life. If you would like to follow along, feel free to come with me. My goal is to post photos of my life, reflections on the world or whatever topics have me up at night, reviews of the long backlog of books I need to get through, and my opinions on music and movies. I am going to figure out how to, in incremental steps, find replacements for the things I’ve relied on social media for, and maybe detail them here. All I know is that I feel ready for it.

Thanks for reading.

Footnote from March:

In the time since I initially wrote this, I’ve had a steady media diet of bad news. It’s come my way with such force and speed that I’ve had little time for anything other than panic, dread, and resentment. It’s probably the worst my mental health has been since 2020. What I’ve said here, on reflection, is more true for me now than it was even a few weeks ago. I will say directly that I am scared and will continue to be scared in the coming months and years, but that allowing my zone to get flooded (a la Steve Bannon, ugh) has set me on edge in a way that has made it necessary for my mental well-being to better align my life with my values, and that has required setting my focus more narrowly on what I can change, and away from what I cannot.

I am determined, as far as I’m able to be, not to allow these changes to steal myself from me. I’ve had other dark periods. I remember what 2016 and 2020 felt like, but I am very different now than I was in either of those years. The impulse to retreat and hide is still my baseline, but I don’t want to give in to that, so I am choosing not to. Now, with fascism not at the door but at the wheel, it’s clear to me than the social media and online worlds have not only played an instrumental role in creating the mess we’re in, but are serving to splinter and distract us from the work in front of us if we are to fight for a country worth living in. And that goes for all of us, not just Americans. Unfortunately, this issue is global. I don’t know that I’ll bunker down here in the States forever and weather the storm in the eye of it, but no matter what, I am forever changed by the last decade and what it has taught me, and I can never look away. So I am shifting my view, but not closing my eyes.